In celebration of Native American Heritage Month, we share researched stories of three local individuals who illustrate resiliency of character and accomplishment. The world that many Native Americans knew for generations had changed dramatically, especially in the 19th century for many Washington Native tribes. The people highlighted here show the range of those who adjusted to such changes and those who resisted it.

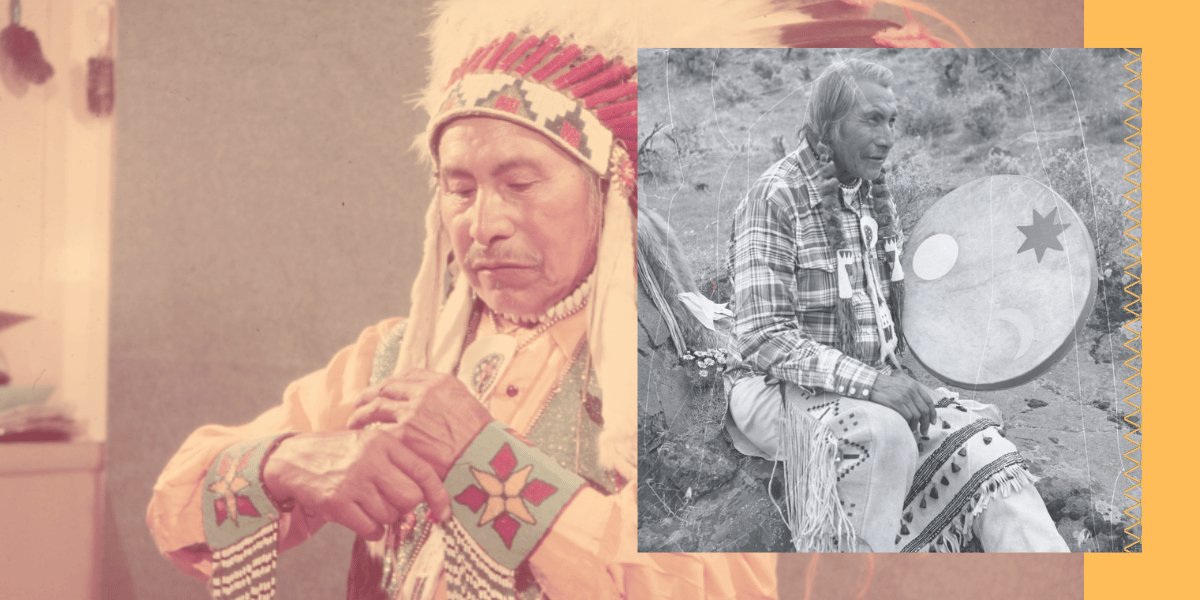

Alex McCoy, “Owl Child” b.1835-d.1939

Alex McCoy was born in 1835 and lived to be 104 years old. Born into the Wasco-Wishram tribes, he was a cowboy for the legendary cattle rancher, Ben Snipes (who has a statue in Sunnyside besides a preserved log cabin). McCoy moved to Montana to live with the Piegan Tribe, where he earned his Native name Owl Child and became a shaman. He witnessed the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn and became a paid government scout during the Modoc Wars. During his time there, he also claimed to invent the sport of bulldogging, or steer wrestling (though some sources contradict the claim). He spoke eight languages and spent most of his life in the Yakima area where he worked as a horse rancher, policeman, and judge. His likeness can be seen on a mural in Toppenish.

Smohalla, b.1815-d.1895

Smohalla was born near Wallula, Washington; he was a member of the Wanapum tribe that existed along the Columbia River from the east of Yakima to the Oregon border. Considered somewhat of a troublemaker who got into personal conflicts with others, his life changed course when he went on a spirit journey, leaving perhaps as far south as Mexico before he returned with a vision for a religion. He spoke of the Great Spirit – the Great Spirit who urged the Natives to reject white man’s teachings and to go back to old Native traditions. History records their worshipful dancing and singing on Sundays; they believed that if the Great Spirit approved, He would make the white settlers disappear, and all the dead would rise and reunite with their families. The religion was referred to as a “drummers and dreamers” belief because drums and dream visions were core to the religion. The famous Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce counted himself as a member of the faith.

The religion caught on among Smohalla’s Wanapum and Yakama followers, and though they were otherwise pacifists, the conflicting beliefs caught the attention of the American government. General O.O. Howard visited the area to assess the state of mind of local tribes. The meetings were largely positive and peaceful but during that time, a murder of a white couple outside of Yakima City became sensationalized in the local media; the culprits were unknown Natives. Because of his leadership and famed symbolism for rebellion among Natives, Smohalla was confined to Fort Simcoe to keep him safe from hateful blame among people living in Yakima City. Smohalla, fearing that an angry mob might come and lynch him, disappeared into the night, escaping Fort Simcoe.

His religion lived on, however, and despite its apocalyptic predictions, the followers continued to live as pacifists, as drummers and dreamers.

Puck-Hyah-Toot (Johnny Buck), b.1878

When Wanapum religious leader Smohalla died in 1895, his son Yoyouni became the leader of the Dreamer religion. In 1917, Yoyouni died during a hunting trip in the winter snow and his cousin, Puck-Hyah-Toot became the next and last prophet of the Dreamer religion.

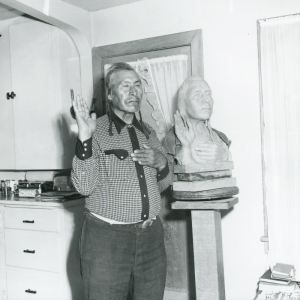

Puck-Hyah-Toot, also known as Johnny Buck, was born in 1878; he was a steadfast follower of Smohalla throughout his life. Puck-Hyah-Toot was a gentle man who befriended Yakima reporter, Click Relander. Relander became an ardent defender of Wanapum and Yakima rights. (His personal collection is the centerpiece of the Yakima Valley Library’s archival collection.)

Puck-Hyah-Toot was never combative with the United States government, but he always spoke up for Wanapum concerns, such as access to fishing and protection of their burial grounds. These were all were encroached upon by the nuclear activities at Hanford, by the dam construction on the Columbia River, and the establishment of the Yakima Firing Center, to which Puck-Hyah-Toot lamented that his people could no longer access the land where the sun set.

Despite these major setbacks, Puck-Hyah-Toot established a constructive relationship with government officials of the day, saving the ancestral burial grounds and a place to fish. Puck-Hyah-Toot was heartbroken to say that everywhere the Wanapum went, someone told them to leave. By the time the tribe settled to Priest Rapids, there was nowhere else for them to go; yet it was at Priest Rapids that Puck-Hyah-Toot’s efforts were successful to establish a permanent home for the Wanapum, where they live today.

The Buck family are still known as an active family in the Wanapum community. A sculpture bust of ‘Johnny Buck,’ made by Relander, is displayed in the Wanapum Heritage Center.

-Written by Matt Kendall, Archive Librarian

For more fascinating stories archived in YVL’s Northwest Reading room, visit Yakima Central Library Monday – Friday, 9am – 6pm and Saturday by appointment. Learn more about this service online or email us at .

References:

Emerson, S. (2010) “Wanapum People After Smohalla”, Historylink.org, accessed in 2023: https://www.historylink.org/File/9524

Kuykendall, G.B. (1960), Manuscript, transcribed by Click Relander. Accessed 2023: https://archives.yvl.org/items/5737b400-1ab6-49f2-bf3e-101bc9feab66

New York Times (June 16, 1939). “Alex (Owl Child) M’Coy; Yakima Indian, a Centenarian Inventor of Rodeo Trick.”

Relander, C. (1956) Drummers and Dreamers. Caxton Printers.

Ruby, R. & Brown, J. (1989) Dreamer-Prophets of the Columbia Plateau – Smohalla and Skolaskin. University of Oklahoma Press.

Toppenish Review-Independent (April 28-29, 2007, supplement April 25, 2007). “Owl Child Remembered – Granddaughter Shares Recollections of Alex McCoy.”

Weekly Pacific Tribune (August 7th, 1878, Aug. 7) “Moses and Smohalla.” Transcribed by Click Relander. Accessed 2023: https://archives.yvl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/57db3a83-d54d-430d-a540-f1e91cf68d27/content